Life

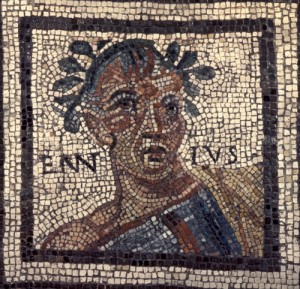

Quintus Ennius was born in 239 BCE at Rudiae (now Rugge) in Calabria (now Apulia). Growing up in a region heavily mixed with both Greek and Italian cultures, Ennius could speak Greek, Latin, and even Oscan, for which he said of himself that he had “three minds.”

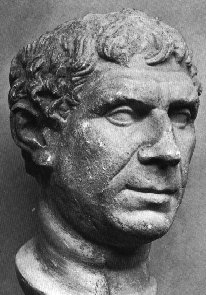

Having joined the Roman army in 204, he may have seen the end of the Second Punic War, and there met Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Elder), who was impressed and brought Ennius back to Rome. There he became associated with Nobilior and Scipio, who acted as patrons for his poetry.

He died of gout in 169 BCE, soon after finishing his Thyestes. He was cremated on the Janiculum, though some ancients mention that his bones were returned to Rudiae. It was also said that he was placed in the tomb of the Scipios, though that is probably a legend. The tufo statues found in the tomb contradict the ancient testimony of a marble statue of him being there.

Works

Unfortunately, like almost all other writers of this time period, his works do not survive the manuscript tradition, and we can only judge their content by quotes found in later authors.

Ennius’ most well-known and quoted text are the Annales, eighteen books of Roman history in hexameters. This history would fast become the authoritative version of Rome’s rise from the fall of Troy (and thus the Trojan migration to Italy) up to the censorship of Cato. The popularity and authority of the Annales led to hexameters replacing Saturnian verse as the preferred meter of epic (and epic-like) poems.

Ennius devoted most of his literary output to plays. He was said to have written twenty tragedies, including the aforementioned Thyestes. Additionally, he authored at least two fabulae praetextae and two fabulae palliatae.

Minor works of Ennius include four books of Saturae, which are among the earliest preserved (albeit in only a few fragments) after Naevius’; Hedyphagetica (lit. “Pleasant Eating”), which appears to be a book in hexameters on dining; Sota, perhaps a parody work; Scipio, an encomium for Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, most likely for his victories in the Second Punic War; Euhemerus, which promulgated the religious beliefs of Euhemerus of Messina a few centuries prior; Epicharmus, written in trochaic septenarius, presumably about the famous Coan comic playwright; and finally, Protrepticus (or Protrepticum, lit. “Exhortation”), about which virtually nothing is known. He may also have written epigrams.

Ancient authors also knew of another Ennius, a grammarian, from the late second century. Works concerning grammar and meter attributed to Ennius were likely written by the latter grammarian, not this poet.

Legacy

Of all the old Latin authors, Ennius was the best received. Conte notes that he was “the most quoted, admired, criticized, and revived.” A century later, Cicero would still call him the summus poeta (“supreme poet”), and he would not be cast aside until Vergil’s polished Aeneid, which supplanted the Annales as the definitive epic of early Rome.

Apart from the Annales, his greatest contribution to Latin literature would be to introduce to the Romans the Greek hexameter. Before Ennius, Saturnian meter was standard, so that even the Odyssey, composed in Greek hexameters, was translated by Livius Andronicus into Latin using Saturnians.

Ennius also pioneered the use of Greek names and words in Latin epic. His invocation of the Muse transliterates, rather than translates the name as Musa (earlier, Andronicus had called her Camena).

After Vergil’s Aeneid, his influence as an epicist waned, and his successor’s polished style became the gold standard for both Latin epic. Quintilian makes a famous analogy about Ennius being an old and venerable tree in a sacred grove: withered, yet still impressive (Inst. Orat. 10.1.88), implying that Vergil was the more beautiful, newer tree.

Online Texts

Latin: PHI Latin Texts

Latin: Forum Romanum

English: Attalus.org

English: Sophrosune Blog

Further Reading

- Michael von Albrecht 1999. Roman Epic: An Interpretive Introduction. Brill.

- Robert A. Brooks 1981. Ennius and Roman Tragedy. Arno Press.

- Sander M. Goldberg 1995. Epic in Republican Rome. Oxford University Press.

- Sander M. Goldberg 2010. “Fact, Fiction, and Form in Early Roman Epic,” in Epic and History (eds. David Konstan & Kurt Raaflaub). Blackwell.