Life

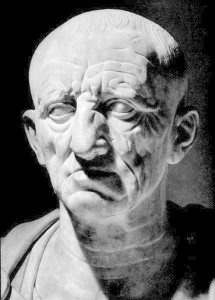

Marcus Porcius Cato, born in 234 BCE, was a prominent Roman politician during the Punic Wars, and is often referred to as Censorinus (the Censor) or Maior (the elder), a later convention which distinguishes him from his grandson Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (named so because he died in Utica).

Cato was born in Tusculum, an old Latin town tucked away in the Alban Hills roughly ten miles away from Rome, into an upcoming plebeian family originally from Arpinum. While Cato himself became consul and even censor, he was a novus homo, “a new man,” the first of his family to achieve consular rank.

Cato’s early childhood is marked primarily by his rural setting and his poverty relative to other men of distinction. This is not the abject poverty that entails homelessness and hunger, but merely the lack of purchasing power and influence in even local circles. Such a childhood most likely had a profound effect on Cato’s outlook, which was defined by traditional virtues enumerated in Cicero’s Pro Sexto Roscio (25) in praise of the agrarian lifestyle: parsimonia (frugality), diligentia (diligence), iustitia (justice, fairness). On the other hand, it would set him up as a reactionary among peers who, on account of Roman domination in the Punic, Macedonian, and Illyrian wars, had newly found wealth, power, and luxury beyond any time prior.

Cato himself played a large part in these wars. During the Second Punic War, he was in Sicily as tribune under the command of M. Claudius Marcellus when Syracuse was sacked in 212; he might have been present with Q. Fabius Maximus during the siege of Tarentum in 209. He was also present in 207 under C. Claudius Nero when the Romans destroyed Hasdrubal’s army, effectively ensuring a Roman victory in the war.

In 204, Cato was elected quaestor and served under P. Cornelius Scipio, who would later go on to capture Carthage and gain the cognomen Africanus. The ancient author Plutarch records a dispute between them, but as historian Alan Astin notes, other sources do not back him on that claim, and Plutarch’s account (which has Cato leave back to Italy) cannot be reconciled with known facts. The account was probably made up based on later antipathy Cato had toward Scipio.

Also of note, at the end of his quaestorship, Cato supposedly went to Sardinia, where he met Quintus Ennius, who later would have tremendous importance in shaping Roman literature.

Like all the other eminent Romans at the time, Cato ascended the cursus honorum, becoming aedile in 199 and praetor in 198, in which he governed the province of Sardinia. It was in his praetorship that he gained notoriety as a strict commander, always adherent to the letter of the law and living a rather Spartan lifestyle, saving money, he claims for the Roman treasury, which paid for its commanders’ expenditures.

Cato finally took command of his own legions in Hispania (mod. Spain), when he was elected consul in 195 BCE. There he came into conflict with various Celtiberian tribes who renewed their rebellion against Roman dominion in the region.

Although some historians have been overly critical of Cato’s competency as a commander—using his own partially exaggerated account against him—there is no doubting that in Rome he was seen as ultimately successful and was subsequently granted a triumph.

After his consulship, Cato was still active militarily, serving M’. Acilius Glabrio against the Seleucids and Aetolians and fighting in the Battle of Thermopylae in 191 (not to be confused with the famous battle of the 300 Spartans against the Persians).

Ten whole years went by from Cato’s consulship to when he was elected censor, the highest of the Roman magistracy, and it was in this position that Cato solidified his stature for posterity. The austerity and strictness he was known for before were at their apex in his censorship, where he, along with his longtime ally L. Valerius Flaccus, had the ability to fine citizens and remove senators from their esteemed positions for offenses of a moral nature. One such action was the removal of L. Quinctius Flamininus, a distinguished citizen in his own right as well as the brother of T. Quinctius Flamininus, who had defeated the Macedonians at Cynescephalae in 197; his crime is debated, but opinions on it range from pederasty to execution of captives during his attacks on Gallic tribes (Livy 39.42).

Part of his austerity which has attracted much debate is his feelings toward the Greeks. Both ancient and modern historians have tended to see Cato as a champion against the encroaching Greek lifestyle. This is an oversimplification, though, and other Hellenophiles (like Lucilius) contain proscriptions against being too Greek-like. Moreover, Cato’s antipathy Greeks doctors, who he claimed were all out to kill Roman citizens, was more against new doctors than Greek ones per se. Other incidents, such as Cato railing against learning Greek, was contradicted by statements that he taught his son Greek letters and by the fact that he knew both the Greek language fluently and was familiar with Greek literature early on in his life.

Cato also seemed to have had personal enmity toward Scipio Africanus, whom many believe to be a Philhellene. Cato’s prosecutions of Scipio in legal courts, however, failed, as the Roman people could not or would not convict the commander who saved Rome from Hannibal.

When seen in his larger context, Cato’s actions are not as sharp as they appear. With his family originally hailing from Arpinum before moving to Tusculum, Cato, much like Cicero later would, was on the margins of the Roman elite. The conquests of Marcellus over Syracuse in 212, Fabius Maximus over Tarentum in 209, and Titus Flamininus’ conquests in Greece in 197 led to an enrichment of these already wealthy and elite commanders from good noble families and an abundance of Greek art in Rome. Cato, being born of low stock, was the first in his line to become consul (a title called novus homo). This would fit in with his personality as recorded by both Plutarch (Cato Maior 1.3), who claimed that Cato always went about “boasting.”

His reactionary stance likely stems from this marginalization, and at least in part it is an act. Whenever he talks about the moral goodness of being a peasant farmer, it should be remembered that in his manual on agriculture, that “farmer” is more manager than tiller. The curse against Greek art is more a curse against luxury—an actual controversy around that time—which the elites he railed against would have been able to afford more than he.

Although, that is not to say that it is not at least in part genuine.

In his latter years, he became a prolific author, an important statesman, and is well-known to posterity for always stating that “Carthage must be destroyed” (Carthago delenda est as it is well-known today, though his actual words are up for debate). He died in 149 before the end of the Third Punic War.

Works

During his own lifetime and thereafter, Cato was famous for his orations. As a senator, Cato would have been expected to give some speeches on a variety of political events, and his extraordinary career as a novus homo and censor furnished him with plenty of opportunities. Combined with his passionate and emotional character,

The only complete work of Cato’s that has come down to us through the manuscript tradition is his De Agri Cultura (“On the Cultivation of the Field”), a treatise of sorts on farming and husbandry. Not only is this the oldest agricultural treatise written in Latin, but it was also the oldest Latin prose transmitted down to us in full.

The very nature of the document is subject to many debates. Some even call into question whether it ever was meant to be published. On the one hand, it is very jumbled, with repetitions and a lack of solid ordering. On the other hand, it has a preface indicating at the very least that it was intended to be published; the disordered nature likely stems from the fact that Cato was pioneering Latin prose convetions, and thus we cannot expect of it a more mature composition.

Oddly included in the work is an encomium to cabbage.

No other complete works of Cato survive, though a good portion of his Origines and a couple speeches survive in part from quotations.

The Origines (“Origins”) is a history of Rome in seven books. The first three books are origins properly, first of Rome and then of various Italian cities. The last four books chronicled Rome’s rise primarily through origins stories and conquests. Roman historian Cornelius Nepos recorded that:

“the fourth is related to the first Carthaginian (i.e. the First Punic War) war; in the fifth the second; and all these subjects are treated in a summary way. Other wars he has narrated in a similar manner, down to the praetorship of Lucius Galba.”

Nepos must not have had the text in front of him, though, since Cannae was narrated in the fourth book and his speech Pro Rhodiensibus was included in the fifth; the Pro Rhodiensibus also partly survives in quotation from Aulus Gellius. The events also continue down throughout Cato’s life, who died presumably while continuing to work on it.

The Origines are quite likely the first prose history written in Latin. Cato’s immediate predecessors wrote in Greek, although a Latin translation of one by Fabius Pictor was known; how early the translation was made is unknown.

The work was unusual for its time. Other Latin historical works were all poetry, written like epic poetry. Other Latin prose works took the form of chronicles maintained by the pontifices, priests of the city of Rome, led by the supreme priest, the Pontifex Maximus. Cato excised religious and natural matters from the work, focusing instead on a military history, which would have been natural for a soldier like him.

The work was also highly unusual in that Cato largely left names of commanders out of the work. Instead of ‘Scipio,’ ‘Fabius Maximus,’ and ‘Hannibal,’ their names were substituted with their position, so ‘consul,’ ‘general,’ and ‘enemy general.’ His rationale was that he meant to glorify the Roman people and state, rather than individuals. However, he included a lengthy description of his own successes in Hispania, and so some see a self-serving motive underlying the proscription against names.

Finally, the unity of Rome and the rest of Italy in the first three books seems to indicate that even at such an early date the history of Rome and all of Italy were intertwined in the Roman imagination. This would be a transition from seeing Rome as a city with power over other peoples to seeing Rome as the capital of Italy, with power over non-Italians.

Also survive many fragments of Cato’s speeches, from a total of around 150; around 80 titles survive today. Extensive chunks of Pro Rhodiensibus (“For the Rhodians”), in which Cato persuaded the Senate not to go to war with Rhodes, though they did not join the Romans in their war against Perseus, were quoted by Aulus Gellius, who himself was commenting on a commentary on the speech by Tiro, the secretary and freedman of Cicero.

Some of these would have been inserted into other works, e.g. Pro Rhodiensibus was included in the fifth book of the Origines.

Other titles known to us are the De Re Militari (“On Military Matters”), Praecepta ad Filium (“Precepts to his Son,” doubtful though), Carmen de Moribus (“Song on Mores”), and Dicta (“Sayings”).

Legacy

Cato had a huge effect on Roman society. His austerity was admired by many in later generations, and his grandson, also named M. Porcius Cato, followed him in that vein. On his account, Carthage was utterly destroyed, rather than merely defeated. Because of his writings, he is unique in our understanding of pre-1st century BCE Romans.

More important for Latin literature, Cato was one of, if not the originator of Latin prose. It would be decades before prose works would equal or surpass his original ventures in this area. If he did bring Ennius to Rome, he would also have a hand in poetry, as well. He was still being read by Cicero and later generations for his oratory, which would not have been surpassed until the Sullan era, when a more polished rhetoric was brought in by Q. Hortensius Hortalus.

His austerity also led him to be seen as a sort of reverent figure, and his Praecepta and Dicta were plagiarized and interpolated, with works like the Distichs of Cato, sayings in two lines, passed around as his.

Quotes

- Carthago delenda est! “Carthage must be destroyed!” Supposedly uttered after each speech leading up to the Third Punic War.

The Elder Cato Online

Latin: PHI Latin Texts

English: LacusCurtius

Further Reading

- Alan E. Astin, Cato the Censor. Oxford, 1978.

- T. J. Cornell, “Cato the Elder and the Origins of Roman Autobiography” pp. 15–40, in Smith & Powell (eds.), The Lost Memoirs of Augustus and the Development of Roman Autobiography. Swansea, 2009.

- T. J. Cornell, ed. The Fragments of the Roman Historians in 3 vols. Oxford, 2010.

- Andrew Feldherr, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Historians. Cambridge, 2009.